The Environmental Justice Movement - Part Three

Natural Resources Defense Council

TITLE: The Environmental Justice Movement – Part Three

AUTHORS: Renee Skelton and Vernice Miller, with contributions by Courtney Lindwall

COPYRIGHT: Natural Resources Defense Council, https://www.nrdc.org/stories/environmental-justice-movement (accessed 4/19/25)

PERMISSION TO USE granted by the NRDC per online guidelines.

The Natural Resources Defense Council was founded in 1970 as the first national environmental advocacy group to focus on legal action. The NRDC helped pass the 1972 Clean Water Act and has since grown to more than three million members and online activists utilizing the expertise of some 700 scientists, lawyers, and other environmental specialists to:

· confront the climate crisis,

· protect the planet’s wildlife and wild places,and

· ensure the rights of all people to clean air, clean water, and healthy communities.

On August 22, 2023, the NRDC published an article titled “The Environmental Justice Movement.” It is a well-written summary of “an important part of the struggle to improve and maintain a clean and healthful environment.”

THE ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE MOVEMENT – PART THREE

The push to advance the environmental justice agenda nationally

By 1990, leaders of thegrowing environmental justice movement, who had chiefly relied on coalitionbuilding and community empowerment, began to look for allies among the traditional, primarily white—and more well-resourced—environmental organizations. These were groups that had long fought to protect the wilderness, endangered species, clean air, and clean water. But they had had little or no involvement in the environmental struggles of people of color. That year, several environmental justice leaders cosigned a widely publicized letter [click Download Resource File above] to the "Big 10" environmental groups, including NRDC, accusing them of racial bias in policy development, hiring, and the makeup of their boards, and challenging them to address toxic contamination in the communities and workplaces of people of color and the poor. As a result, some mainstream environmental organizations developed their first environmental justice initiatives, added people of color to their staff, and resolved to take environmental justice into account when making policy decisions. All of this remains a serious work in progress.

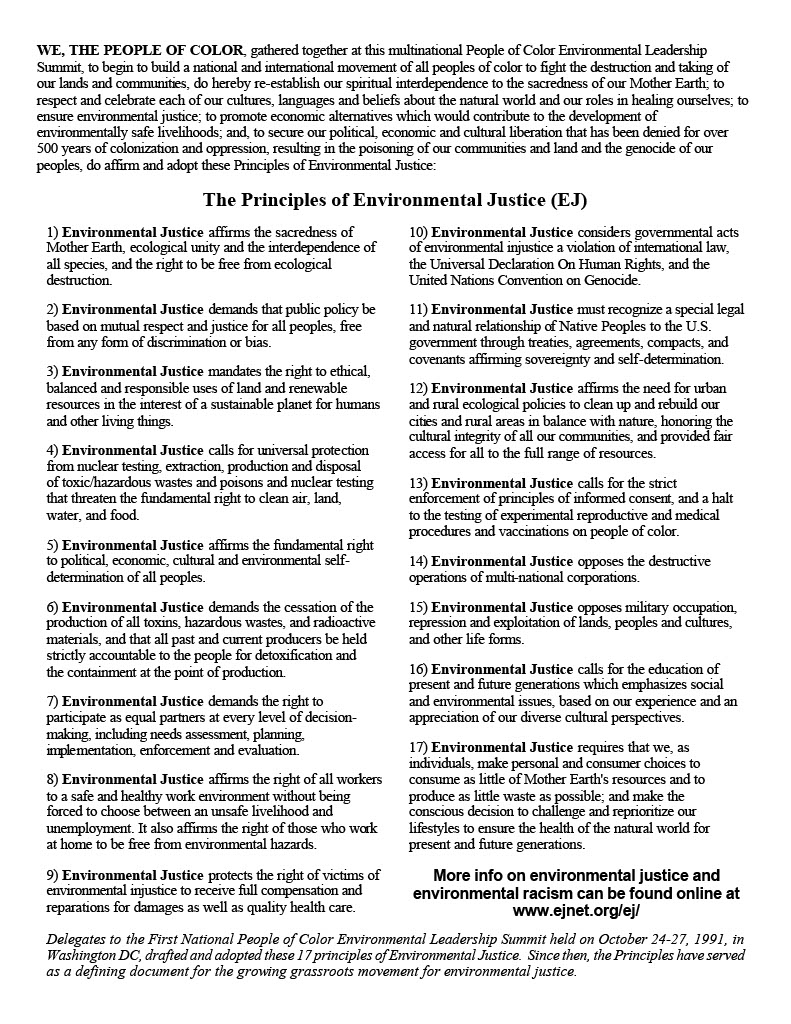

Environmental justice leaders also pushed their agenda within the government. In 1990, a meeting between a group of prominent academics and advocates within the movement and a top official in the first Bush administration led to the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Environmental Equity Workgroup. The following year, the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit brought together hundreds of environmental justice leaders from around the world to Washington, D.C., to network and strategize for the first time. The list of attendees—which included Reverend Jesse Jackson, Dolores Huerta, Cherokee Principal Chief Wilma Mankiller, and the heads of NRDC and the Sierra Club— demonstrated that environmental justice was beginning to be taken up by many in the American mainstream. What's more, the summit produced the "Principles of Environmental Justice" [see below] and the "Call to Action," two foundational documents of the environmental justice movement.

By 1992, when Bill Clinton became president, it was clear that environmental justice was becoming important to leaders of a core constituency of the Democratic Party. Clinton appointed two leaders, Chavis and Bullard, to his natural resources transition team, where they helped make environmental justice an important part of the president’s stated environmental policy. And then, on February 11, 1994, Clinton signed Executive Order 12898—a groundbreaking order directing federal agencies to identify and address the disproportionately high adverse health or environmental effects of their policies or programs on low-income people and people of color. It also directed federal agencies to look for ways to prevent discrimination by race, color, or national origin in any federally funded programs dealing with health or the environment. What began in the streets of Warren County had made it to the White House.